After our Christmas drinks and mince pies a large gathering (98 people) of the Bristol Branch of the Historical Association had a great end to a very successful term of lectures. Andrew Foyle is the author of two volumes of the Pevsner Guide covering the City of Bristol and North Somerset. He is an acknowledged expert on the architecture of the city and has worked on the renovation of many of the city’s distinctive buildings. He presented his personal choices grouping together the Lodge Houses, like Red Lodge, and the timber framed houses many of which still survived. He covered the middling sized Bristol country houses like Stoke House (Stoke Bishop), Langton Court (Brislington), Oldbury Court (Fishponds), Henbury Great House and Old Sneed Park. Many of them were ‘old fashioned’ compared with houses built in London or other parts of England. However, Kings Weston House was a one off. It was built by Sir John Vanbrugh the architect of Castle Howard and Blenheim Palace.

Andrew then moved back into the city to look at Town Houses such as Elton House (St James Barton) and Churches and Chapels. These included Christ Church with St Ewen on Broad Street where the Paty family brought their skills as architects and craftsmen and the contrasting chapels. The nonconformist chapels were often austere from the outside but some contained elegant interiors. Next the Gothick grottos of Goldney House and Crew’s Hole were explored and Black Castle and Arnos Court where the Paty influence was again on display.

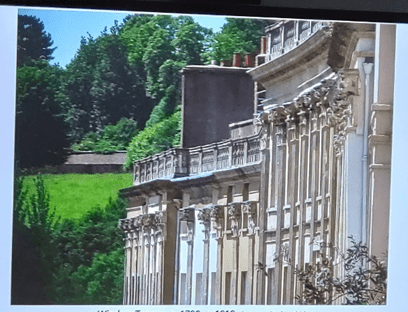

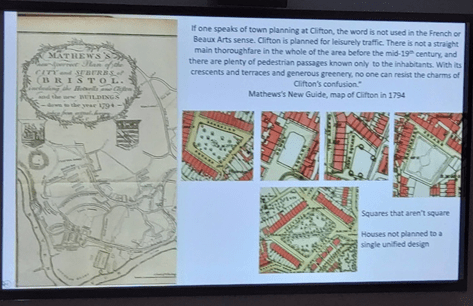

A particular highlight of the lecture was the exploration of Clifton. Even the austere Pevsner had admitted ‘no-one can resist the charms of Clifton’s confusion.’ Andrew demonstrated that unlike the better known Bath, Clifton contained squares that weren’t square and homes not planned to a single unified design. Its mishmash of styles and the disaster of a bank crash in the 1790s had led to the scaling down of Windsor Terrace and the Royal York Crescent (reputed to be the longest crescent in Europe). The way that Bristol architecture responded to its landscape was breathtaking in Andrew’s slides.

Sadly, the clock was now ticking so Andrew dipped into his examples from the 19th and 20th century for two amazing buildings. The Granary on Welsh Back built by Ponton and Gough was described ‘as working machine’ for drying grain and finally the ‘Council House’, now City Hall. This building by Emmanuel Vincent Harris was begun in the 1930’s and finally opened in the 1956. Andrew demonstrated that in fact the delays to build a new town hall (originally proposed in the 1880s) had been going on for decades before and a range of sites had been considered before work finally began in 1936. He showed us the beautiful furniture and interior designs from the Council House, some of which had now been returned to their original locations due to a research project he worked on. He also corrected some of the convenient myths around the statue of Cabot and those gilded unicorns on the roof which had always been in the original design.

His conclusions rang true for many of us living in Bristol. Bristol’s unique character was insular, conservative and behind the curve of fashions. It was dominated by a few aristocratic families or estates. It was governed by a mercantile oligarchy of inter-dependant families. However it tended to inertia in decision making. It relied on home grown architects and builders. Its city and hinterland were full of piecemeal development and as result there tended to leave piecemeal survivors from previous eras. Although Bristol was industrialised there was no one dominant industry. Bristol has surviving pre-industrial elements including medieval churches and timber framed houses. A truly unique city.