Lecture by Professor Simon Potter 5th March 2025

Professor Simon Potter gave us a fascinating lecture on Wednesday about the BBC’s role in what is known as ‘soft power’ and its relationship with British Foreign Policy. It challenged many of our preconceptions about the BBC which are based very much on what we watch and listen to in the UK. He also looked at the view that the BBC was a safe and unbiased broadcaster. Its development from the wireless production company the British Broadcasting Company of 1922 to its royal charter in 1927 as a public broadcaster and its links to the monarchy from 1932 were traced.

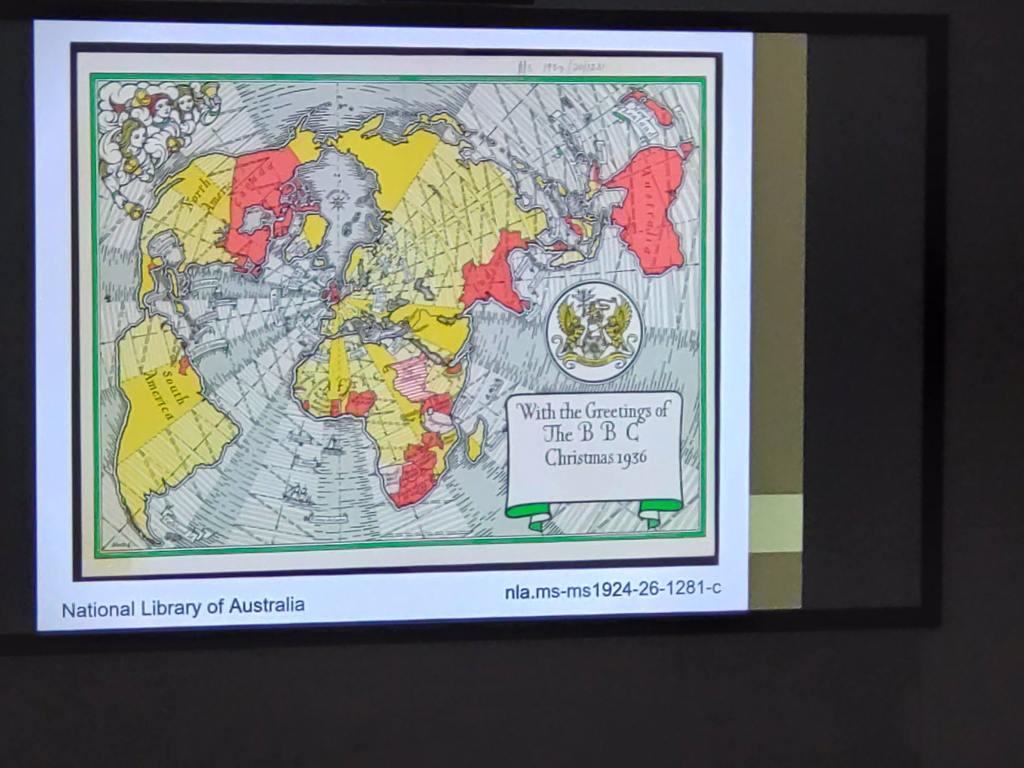

He showed how the BBC set up a relay network of radio stations all over the globe and as the empire was wound down this were increasingly located in remote locations. In particular he looked at how the BBC evolved its World Service from an overseas broadcast for the Empire into the multilanguage broadcaster. Also, how it developed an Arabic service in 1939 and a Portuguese and Spanish service aimed at Fascist countries in the late 1930s. The BBC radio service’s role in wartime was riveting in particular the influence of the World Service on America and in turn the introduction of soap opera with Front line family on the advice of American broadcast experts. During the Cold War the Foreign Office’s role in subsidising the BBC’s World Service showed the blurring of ‘soft power,’ information and propaganda. This included paying for the BBC to record on vinyl some of its greatest radio hits like the Goon Show and Take it from Here. Something like 25% of World Service programmes were actually Foreign Office funded. In the second half of the lecture Simon showed how the more expensive medium of television took a very different path with BBC enterprises selling flagship programmes like the Forsyte Saga and Civilisation to the USA. Simon brought the subject right up to date with the cuts to the World Service under David Cameron and re-emergence of radio because of the internet. The BBC’s identity as a neutral broadcaster was questioned but we were also reminded of its achievements. It’s future was queried. Our audience shared some of their experiences of the BBC including one former employee and some lively questions were asked and answered.